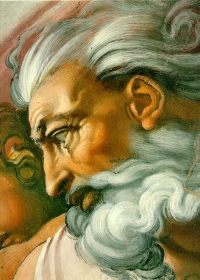

This image is a part of Creation of Adam

by Michelangelo as shown in the Sistine Chapel.

Wikipedia

Supreme Being

The Supreme being is typically a patriarchal figure, often a sun god, sometimes husband to a great goddess. He is the creator and giver of life, representing all power and authority, as well as ultimate reality (Leeming, World of Myth 124).

The major monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are based on one supreme deity. In the monotheistic religions, Yahweh and Allah are omnipresent, omnipotent, omniscient beings. In the Old Testament, God is seen primarily as a potentate, a king of kings and lord of lords. In his manifestation as Yahweh, he is the "I AM," and throughout the Old Testament, the Hebrew people are constantly reminded not to create images of Yahweh and punished when they succumb to idol worship. Muslims are also prohibited from creating artistic representations of Allah, whom Mohammed named as the one true God (Jordan 12-13). The central tenet of Islam is that "There is no god other than Allah," and Allah is equated with the God of the Jews and Christians (Leeming, Oxford Companion 13). In the New Testament, God is portrayed as the Heavenly Father, watching over his children. But even the New Testament, particularly in the book of Revelation, emphasizes the power and majesty of God.

Polytheistic religions also have a supreme deity, usually seen as an All-Father. For the Greeks, Zeus is the All-Father, but as extensive as his power is, even he is subject to the Fates. The Norse Odin, the Hindu Brahma, and the Babylonian Marduk are all representatives of this type.

Great Goddess

also known as Our Lady of Vladimir

or the Virgin of Vladimir. Wikipedia

Marijas Gimbutas has argued that the earliest religion was a universal Great Goddess religion that was gradually supplanted by belief in a patriarchal warrior god. Based on an interpretation of archaeological evidence from pre-historic, pre-literate sites, Gimbutas argued that early human societies were primarily agricultural and peaceful, emphasizing and valuing the feminine as expressions of the earth's fertility and nurture (LaFont 127). Debate has arisen regarding Gimbutas' views. Some archaeologists disagree both on the numbers of ancient artifacts indicating female worship and their significance. Without a written culture to interpret the artifacts, the question of whether a great goddess religion predominated in the Neolithic world cannot be answered definitively (Leonard and McClure 102-110).

However, many cultures show evidence of the great goddess mother. Greek mythology begins with Gaia; Mesopotamian, with Tiamat; Egyptian, with Nut. Later versions of the goddess emphasize fertility, such as the Demeter myth. In Christianity, the Madonna represents the great mother. David Leeming says

In the stories of the Great Goddess, a pattern emerges in which the Goddess figure mourns the loss of a loved one, goes on a search, and in bringing about a form of resurrection--clearly associated with the planting and harvesting of crops--establishes new religious practices or mysteries for her followers. These mysteries are inevitably concerned with the connection between death, planting, sexuality, and resurrection or immortality on the one hand, and physical as well as spiritual renewal, on the other. (Leeming, World of Myth 135)

, fresco of Dura Europos,

, fresco of Dura Europos,

datable after 168 and before 256 CE, Wikipedia

Dying God

The figure of the dying god is often linked with the great mother. Gimbutas argued that, in fertility cults, the male god was consort to the goddess and sacrificed in a yearly ritual celebrating the cycle of the seasons (Leonard and McClure 187). One of the oldest myths reflecting the dying god is the Sumerian myth of Inanna (Ishtar) and Dumuzi (Tammuz). In a myth similar to the Greek Demeter and Persephone myth, Inanna forces Dumuzi to enter the underworld and free her sister (and shadow self) Ereshkigal from death by taking Inanna's place (Leeming and Page 80).

Other dying gods include the Norse Odin, who is sacrificed on the World Tree and Balder, gentlest of the Norse gods, who is killed by Loki's trickery; the Slavic Iarilo; the Greek god Dionysos; the Egyptian Osiris, who gives birth to his son Horus after his death and resurrection (Leeming, Oxford Companion 110); the Iranian Mithra, a war god popular with the Romans involving a "ritual sacrifice of an ox and a bath of blood that would bring strength and loyalty" (Leeming, Oxford Companion 266); and the Hawaiian Lo-hi-au, who is twice resurrected, once by Hi-i-aka-of-the-bosom-of Pele and again by the male shaman Kane-milo-hai (Leonard and McClure 124-132). For Christians, the greatest example of the dying and reborn God is Christ, who laid down his life for the world in his crucifixion at Golgotha and was resurrected on Easter Sunday as the New Testament Passover lamb.

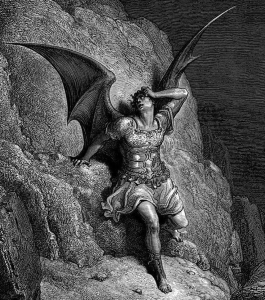

Tricksters

Tricksters are some of the most popular figures in mythology, despite their questionable morality. In Freudian terms, tricksters are instruments of the id, usually male, the con men of mythology, sometimes clever and devious, and other times moronic. Tricksters are "figures of play" (Leonard and McClure 247) "yet the Trickster's playfulness can carry with it serious, even tragic or transcendent, overtones. . . . embodying all the infinite ambiguities of what it is to be alive in the world" (Leonard and McClure 250). The trickster "'combines in his nature the sacredness and sinfulness, grand gestures and pettiness, strength and weakness, joy and misery, heroism and cowardice that together form the human character'" (Erdoes and Ortiz qtd. in Leonard and McClure 250). Tricksters are "moral counterexamples" (Leonard and McClure 250), and in their tales, the "innocent are as likely to suffer as the guilty" making these myths "more realistic than instructional tales usually are" (Leonard and McClure 252).

Satan, Paradise Lost. Wikipedia

Tricksters remind us that, despite our human pretension to nobility and semidivinity, we are inseparable from our bodily urges to eat, excrete, and procreate. At the same time, the Trickster by his very transgressions celebrates and helps maintain the rules, the social structures, which are also central to what we are. And in all this contradiction, the Trickster teaches us to reach for what we desire and to laugh at ourselves when we fall short. (Leonard and McClure 253)

The trickster can be a "creator, culture-bringer, opportunist, mischief-maker, amorous adventurer, hunger-driven manipulator, credulous victim of others' tricks, lazy work avoider, transgressor, [or] clown of the body" (Leonard and McClure 252). Many familiar TV and cartoon characters are tricksters. Wile E. Coyote is a hunger driven manipulator and lazy work avoider as is Yogi Bear. Bugs Bunny is a culture-bringer, opportunist, mischief-maker, and credulous victim of others' tricks (for instance, when he is chased by Marvin the Martian). The Three Stooges are mischief makers, credulous victim's of others' tricks, and clowns of the body. Bart Simpson is an opportunist, mischief-maker, lazy work avoider, transgressor, and clown of the body. Pepe le Peu is an amorous adventurer. Mythological tricksters include Prometheus, Loki, and Satan. A human trickster in the Old Testament is Jacob, who tricks his brother out of his birthright and is tricked in turn by his uncle.